GRV Assessment and Release

Gastric residual refers to the volume of fluid remaining in the stomach at a point in time during enteral nutrition feeding. Caregivers often withdraw this fluid via the feeding tube by pulling back on the plunger of a large syringe at intervals typically ranging from four to eight hours.

Performing manual gastric residual emptying to evaluate patients’ feeding intolerance assumes that higher gastric content correlates to problems with gastric emptying, as observed in 50% of critically-ill patients [1]. However, studies show that gastric residual volume (GRV) does not correlate with incidences of pneumonia regurgitation, or aspiration.

The manual release of GRVs leads to increased enteral device clogging, inappropriate cessation of enteral nutrition, consumption of nursing time, and allocation of healthcare resources and may adversely affect outcome through reduced volume of EN delivered [2].

In fact, reflux events are common and unpredictable, and can be induced by changes in the patient’s position. Even with a half-empty stomach, reflux can evolve into aspiration and pneumonia.

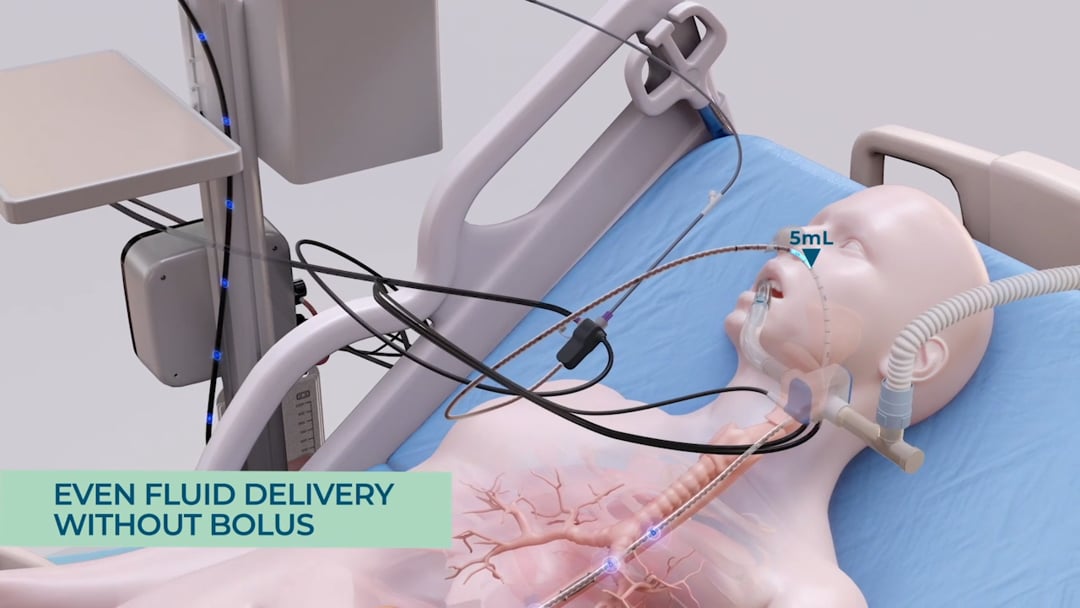

Without real-time monitoring of reflux, even periodic suction at 4-hour intervals will miss random reflux events, putting the patient at risk. Since evacuated stomach content is not compensated, nutrition targets are missed smART+ replaces periodic manual GRV assessments with sensor-based GRV status monitoring and real-time reflux detection.

Before a massive reflux event can occur, the system detects the rising of the gastric content and automatically pauses feeding, so as to not increase the pressure by adding more feeding material to the stomach. This is followed by the opening of a port which enables any excess gastric content to be released into a GRV bag, which is facilitated only through the natural gastric pressure inside the stomach – no suction is being employed. This way the system ensures that only excessive gastric content is being evacuated. As a result, the pressure inside the stomach is being reduced and the reflux can subside. In addition, the system records the drained gastric content and adjusts feeding volumes gradually to compensate for any nutritional losses from the GRV release. This is particularly important as over time, if large quantities of gastric residual volume are extracted and not being replaced, the patient may become at risk for underfeeding and subsequent malnutrition. By automatically compensating for any losses in energy, the system ensures that the patient’s nutritional target is being achieved.

[1] Deane A, Chapman MJ, Fraser RJ, Bryant LK, Burgstad C, Nguyen NQ. Mechanisms underlying feed intolerance in the critically ill: implications for treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(29):3909-3917. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3909.

[2] McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33(3):277‐316.

Global Site

Global Site